Update: Climate Change, Hurricanes, and the Real Costs of Rebuilding in Vulnerable Areas

Are Agencies Leveraging Climate Fear for Taxpayer Dollars?

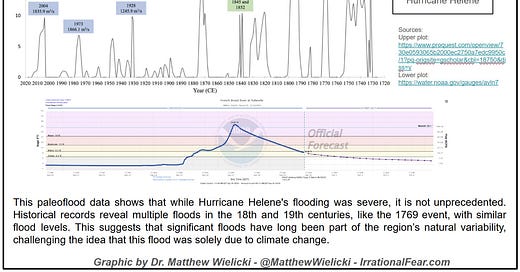

This is an update to the original article, "Climate Change, Hurricanes, and the Myth of the Unprecedented," which can be found below. This update incorporates new data and historical flood events that challenge the prevailing narrative that recent extreme weather events, like Hurricane Helene's flooding, are solely due to climate change.

In the original …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Irrational Fear to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.