The Great Adjustment Debate: Is Climate Data Really Reliable?

Exploring the discrepancies between raw data and adjusted climate records.

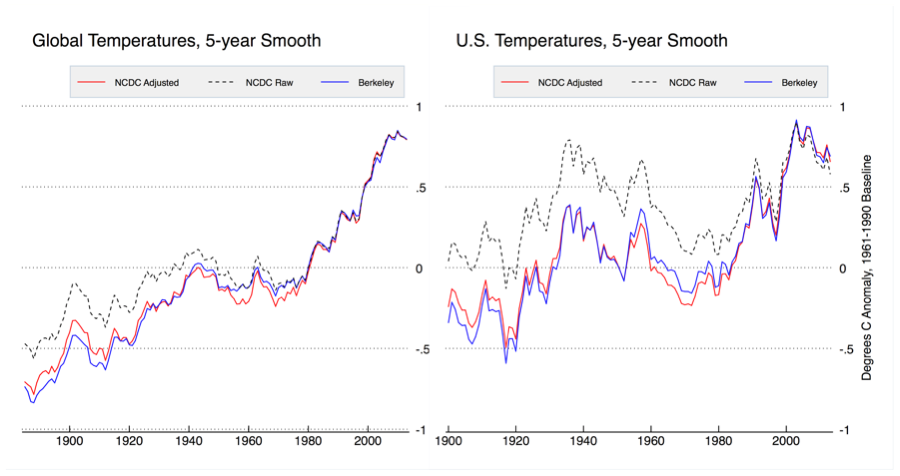

In recent years, the debate over temperature data adjustments has become increasingly polarized. Many question whether these adjustments are made to exaggerate warming trends, while mainstream climate scientists and NOAA argue that they are necessary to correct known biases in historical measurements. To explore this issue, I will compare some different independent analyses of NOAA temp data adjustments.

NOAA’s Position and Modern Adjustments

The U.S. Climate Reference Network (USCRN) was introduced as a modern dataset with state-of-the-art instrumentation designed to avoid the biases found in older datasets. While the USCRN provides more reliable data, NOAA continues to defend the necessity of adjusting historical data. For instance, NOAA’s methods include homogenizing data from older datasets to align them with modern readings, an effort designed to present a coherent historical record. However, critics argue that these adjustments, while intended to address biases, often reinforce the narrative of accelerated modern warming.

Berkeley Earth: Defending Data Adjustments

In their report, Berkeley Earth justifies the need for adjusting historical temperature data by explaining that such data is prone to various biases that can distort long-term climate trends. These adjustments are intended to correct inconsistencies in the historical record to provide a more accurate representation of temperature changes over time. Two major types of bias that Berkeley Earth addresses are Time of Observation Bias (TOBs) and the Pairwise Homogenization Algorithm (PHA).

Time of Observation Bias (TOBs):

Historically, temperature recordings at weather stations were made at different times of day, and over the years, a systemic shift occurred. Before the 1950s, many stations recorded temperatures in the afternoon, but after the 1950s, the observation time shifted to morning at many stations. This change led to a cooling bias in the recorded temperatures, as morning temperatures are typically cooler than afternoon temperatures. The shift, if unadjusted, would create the false impression that earlier decades were warmer than they were compared to modern records.

By adjusting for TOBs, Berkeley Earth and NOAA argue that this bias can be corrected, by raising past temperatures slightly and aligning historical data with modern observations for a more accurate comparison. This adjustment results in a more consistent and reliable long-term trend of temperature change, free from the distortions caused by inconsistent observation times.

Pairwise Homogenization Algorithm (PHA):

PHA is another technique used to adjust for non-climatic factors influencing temperature measurements. Localized factors such as the relocation of weather stations, changes in instruments, or the influence of urban heat islands can introduce artificial changes in temperature data. For instance, when weather stations move from a rural to an urban location, or when modern instruments replace older ones, the data can reflect changes that have nothing to do with climate and everything to do with local influences.

The PHA works by comparing each station’s data to nearby stations that have similar conditions, allowing it to detect and correct for anomalies that may result from these non-climatic factors. This method ensures that temperature records reflect broad regional climate changes rather than localized disturbances or technical changes. Berkeley Earth emphasizes that such adjustments are crucial for constructing a more accurate global temperature record, arguing that without these corrections, the data would be unreliable.

Geophysical Research Letters Review

The 2015 paper published in Geophysical Research Letters titled “Evaluating the Impact of U.S. Historical Climatology Network Homogenization Using the U.S. Climate Reference Network” argues that NOAA’s adjustments are scientifically sound and necessary. It claims that even with significant adjustments, the warming trend remains consistent with the data. However, this study has been critiqued for pushing a specific climate narrative by validating adjustments that systematically create a warming bias, despite acknowledging the data complexities.

It is important to note that NOAA’s methods validate confirmation bias by adjusting historical records to fit the narrative of modern climate models, which project increasing warming. This approach, while designed to improve data accuracy, may obscure natural climate variability and inflate the urgency of climate action. The emphasis on adjustments that warm the present and cool the past raises concerns about the integrity of the long-term climate record.

This practice raises the possibility of confirmation bias, something I have discussed at great length that is inherent in the IPCC, adjusting historical data to align with modern climate narratives. This paper, while endorsing the quality of modern datasets like USCRN, tends to brush over uncertainties and complexities in historical data corrections, framing the adjustments as unquestionably scientific.

Both the USCRN data and NOAA’s historical adjustments thus reveal a tension between refining data quality and pushing a narrative that supports dramatic climate action. These biases are subtle yet significant, and they underscore why a more critical examination of temperature data, and how it’s presented to the public, is necessary before making drastic policy decisions based on potentially skewed records.

MDPI’s Atmosphere Journal: A More Critical View

In contrast to the above reports, the MDPI paper "Evaluation of the Homogenization Adjustments Applied to European Temperature Records in the Global Historical Climatology Network Dataset" questions whether the temperature adjustments made to climate data might be inflating modern warming trends. The paper argues that the methods used to correct historical temperature records may not be as neutral or scientifically robust as they are claimed to be, raising concerns about the accuracy of long-term climate projections.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Irrational Fear to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.